My first memories of my father are of his absence.

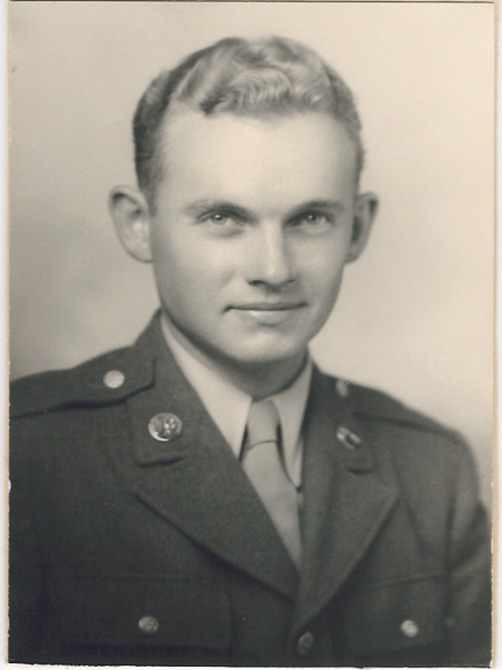

World War Two was raging. He was a soldier somewhere in France, or Luxembourg, or maybe Germany. At times, nobody knew for certain until a letter arrived from the warfront. Written three weeks ago, the letter could only tell us where he had been. We never knew where he was, whether alive or dead, on the day we read it. Time had marched on, and so had Dad, in the infantry of General Patton’s Third Army.

My mother sat on the edge of my bed reading my father’s letters: Tell Jimmy when I get home, I will take him fishing. I closed my eyes and fell asleep dreaming of fishing with my dad, but he was just another word I was trying to learn. I couldn’t picture him at all. He had left for the war before I could remember him.

His last name was Casper, but my grandparents with whom we lived during the war were named Brouse. I thought my name must be Brouse. This turned into a fight. “Your name’s not Brouse –it’s Casper. You’re a Casper!” the neighbor boys shouted. “No, my name is Brouse!” I shouted back. Our voices echoed among purple tree shadows in adjoining moonlit yards as we romped for hiding places in the next game of hide-and-seek.

From a radio high up on a kitchen shelf came noontime news of the war. Noon sounded like moon, so I went outside and looked for noon in the sky. “Where is noon?” I asked my mother. “I don’t see it anywhere.” “It’s on the clock,” she said, pointing up over the kitchen doorway. “It’s the number twelve.” Noon was twelve.

Evenings, my mother and my grandmother sat by a large wooden radio in our living room staring at their shoes or gazing at a wall as if a window were there, and they could see through it into a world the radio talked about.

Mom looked at me and pointed to the radio. “Your daddy is there,” she said. I looked at the radio. Words—Allies, Normandy, Hitler, Churchill, Roosevelt, London, and France—coursed through my brain without finding a home there, just sliding through without catching on anything in particular.

Then a postman coming up our walk patted me gently on the head. Our hometown newspaper had just reported my father missing in action. The month nobody knew where he was I remember as a kind of silence. The ticking of a clock in our dining room grew louder. The large wooden radio was turned off.

Word of my father eventually reached us from a hospital in France. He had been wounded twice. I only remember this from hearing about it afterwards, but I do recall the war ending and the day of his return.

Church bells were ringing, including one in a small white church the other side of my aunt Agnes’s yard in Cleveland, Minnesota where I was playing as the war passed into history. After listening to this for the better part of an afternoon, I asked Aunt Agnes about the church bell. “It’s the end of the war,’ she said, and so it was. Soon my father would be coming home.

The day of his arrival I spent digging with toy shovel and bucket by the back steps of what had been the only home I ever knew. It seems to me there was something hesitant and nervous about this activity which even now I distinctly recall. Perched on the cusp of major change, I sought to distract myself among tiny piles of earth. Years later I captured the moment in a childhood poem:

Homecoming

My father came home from the war.

All day I dug around the door,

Piling mountains dark and high,

My truck on top was in the sky.

A wrinkled worm came out to creep

Through a valley I dug deep.

I tried to get the worm to play,

But in the truck he wouldn’t stay.

Then mother touched my arm.

We drove to where a fleet of buses had parked to unload soldiers coming home. In the back seat, I peered through windows to right and left. I peered between the heads of my aunt and uncle sitting up front, looking for a man I couldn’t remember. The scene all around was jubilant chaos with soldiers in uniform piling out of the buses and heading out in all directions looking for those who came to meet them. Their figures passing through headlights cast long shadows over the street. Somehow my father found us and settled into the backseat beside me. He did what men would do in those days when they met a little kid: he tousled my hair. This is my first memory of the man named Daddy. I was almost four years old.

Life, too, got a good tousle that night and in the following weeks, for everything was rearranged and changed. The world no longer spun around my Brouse family and the Glenwood Avenue neighborhood. We moved out into the country. I was no longer a Brouse, and had become for sure a Casper.

Life, too, got a good tousle that night and in the following weeks, for everything was rearranged and changed. The world no longer spun around my Brouse family and the Glenwood Avenue neighborhood. We moved out into the country. I was no longer a Brouse, and had become for sure a Casper.

For most of us, I think, childhood memories can be especially intense, becoming in some sense the building material of a subsequent life. For a writer, this can lead to novels. If someone asked me why I write so much about children and their parents, especially about dads, I would have to say that I guess I never got over it.

At least I can write about my memories.

Dad, for his part, could never say much about the war. One evening, years afterwards, he did tell me about the second time he was wounded. He was the last man in a group of twelve on patrol along a river when a machine gun opened fire from an adjacent hillside. The eleven men in front died instantly. Had the gunner held his finger on the trigger a second longer, Dad would have been killed. The man dying immediately in front of him left a wife and four children back home.

If his kids are still around somewhere as this Father’s Day approaches, I imagine they are still thinking about him.

Graham Greene once said, “My novels are my children.” My novels are my parents.

Photo: Holly J. Casper, Dad in uniform.

Maria Evans

June 18, 2015 at 5:18 am

I, too, experienced my Dad’s absence and for the same reason. I am about 4 years older than you and found his return had very painful consequences. I did grow to love him, but it took a very long time.

Stella Oelke

June 18, 2015 at 9:42 am

Having been born in 1949, I can not relate to those emotional times that many faced once this dreadful war was over. I only know the after effects of what it can do to your Dad for a lifetime! He is at peace now and so loved in thought and memory! Thanks for sharing your experience it touched my heart….

carleolson

June 20, 2015 at 4:59 pm

Thank you, James, for this. Such a great reminder to my generation (GenXer!) of what so many sacrificed for their families and countries.

Mark Casper

June 20, 2015 at 10:24 pm

Excellent writing Jim. You put me right there with you digging or in the back seat. What a remarkable memory to have. Thanks.